To secure long-lasting successful delivery of peer programs, continuous improvement and knowledge must be a focus. In this regard the ILC toolkit again provides us with insight into the importance of having an internal ‘learning loop’. A learning loop is a defining procedure about how the work you do now informs what you do next. It reflects the fact that learning is an ongoing, repeated process. When you know what you are doing now, undertaking improvement in your peer programs becomes possible.

- Prove your activity provides value: ‘Communicate your findings to funders, beneficiaries, staff and other key stakeholders. Outcomes can’t be achieved overnight, yet you can show that progress is being made.’

- Improve on your activities: use the information to assess if you are on track to achieving your outcomes. In other words, where is it you are currently located? How close are you to your desired destination? ILC suggests that you ask yourself:

- ‘Is the program delivering what it set out to do?

- If not, why not? What needs to change?’

Feedback represents an important way for members to let you know when a problem/s exist. Cultivating a good culture of feedback within your peer organisations is something that has been advised within pre-NDIS state government delivered disability models of support. For example, Disability SA urges providers to ensure they have a feedback and incident review process in place. This process should support people’s rights to safely bring up their grievances without fear of repercussions and be easily accessible. They also assert that feedback provides an opportunity to make services better and safer for everyone. A good feedback culture is where people are encouraged to provide feedback, and they feel comfortable providing either positive or negative feedback about the services they receive.

Growing the capacity of individual participants is a likely key objective for your program. As such, the information you gather from them is going to best employed to inform program design and development. Are you asking your attendees for suggestions of new group discussion topics or information of interest? Do you regularly assess their feedback on locations? This will expose whether levels of accessibility or suitability have changed over time. To ensure a particular participants does not dominate, is the ‘feel’ in the group right? Does feedback suggest the facilitator needs support to learn strategies? It is crucial to have a range of such details gathered if they are some of the drivers of your peer program’s success. Feedback also guides our data collection and analysis decisions, as we will want this kind of information available on a group-by-group basis and/or a topic-by-topic basis. This transforms evidence into a formidable tool for program learning and improvement.

In addition to accumulating information on an assortment of essential program features, it is also important to use the evidence you have collected from individuals whenever it is available. People who have been asked for their opinion want to know it was taken seriously. Some peer group members may be unfamiliar with being asked to provide feedback and being able to share their views within an official assessment process. By being involved, they are trusting their organisation to appreciate their input and treat it with respect for the worthy evidence it is. Everyone wants to feel valued, and I know I would feel more valued if I saw my ideas, efforts and feedback being thought about, reported on, and included in some way. This is also one of the ‘Principles of Good Practice’ identified in the Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC, 2018) practice review: being ‘flexible’ and ‘responsive’. This is discussed back in Section 3, where it is noted that ‘the ability of peer organisations to be responsive to participant needs and preferences is a key factor for their success’. Davy et al (2018, p.11) notes that having such feedback evidence will enable peer programs ‘to respond locally and at a grassroots level to what works’ for specific members and groups.

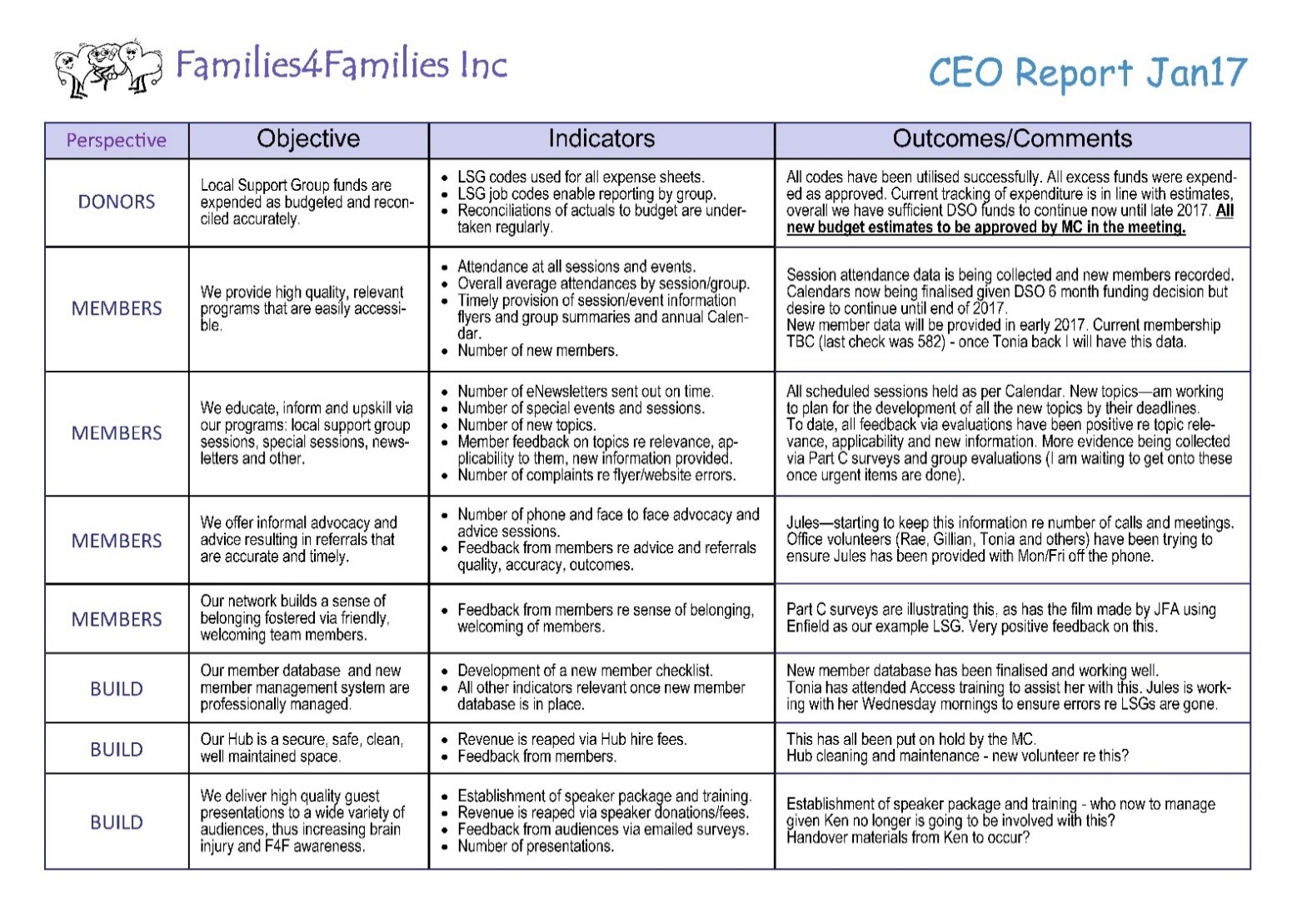

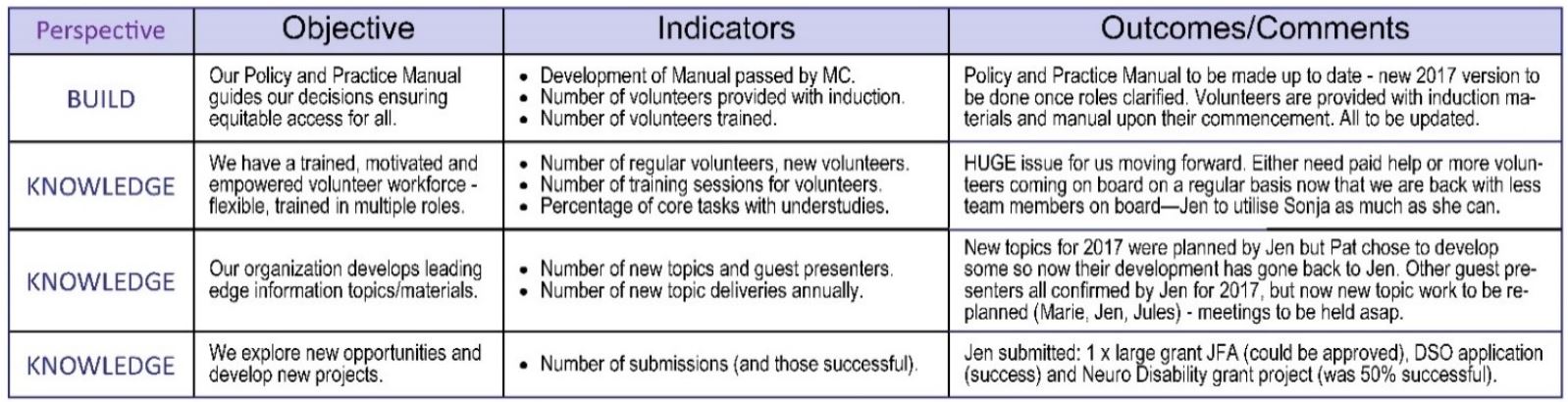

Another of the ‘Principles of Good Practice’ for peer programs identified by the SPRC (2018) review is being a user-led organisation. Also discussed in Module 3, user-led organisations are described as being based on the lived experience of people living with disability and their families. Given this approach, it is uncommon for peer led organisations to have access to experts in areas such as ‘evaluation’ or performance assessment. It is fundamental for us to take simple and straightforward methods of reporting into account for people living with disability, alongside their family and friends, who may undertake the strategic management of the organisation. Guaranteeing that staff share evidence with their organisation’s Board, or Management Committee, is vital. Once more, applying the existing example of Families4Families, the following table was employed in that case, for reporting of BSC objectives performance to the Management Committee (their ‘Board’) ahead of each bi-monthly meeting.

Capsule: Peer organisations can benefit significantly by learning from feedback and your gathered evidence. Continually striving to use what you have done to influence what you will do creates evidence of success.

SELF STUDY Q7.4

Describe three ways that your peer program team learns from its past performance (or three ways that it would like to be able to learn from its past performance).

SELF STUDY Q7.5

Provide one example of a situation where your experience in delivering peer programs resulted in a successful outcome. Do you have any evidence of that success? Why or why not?